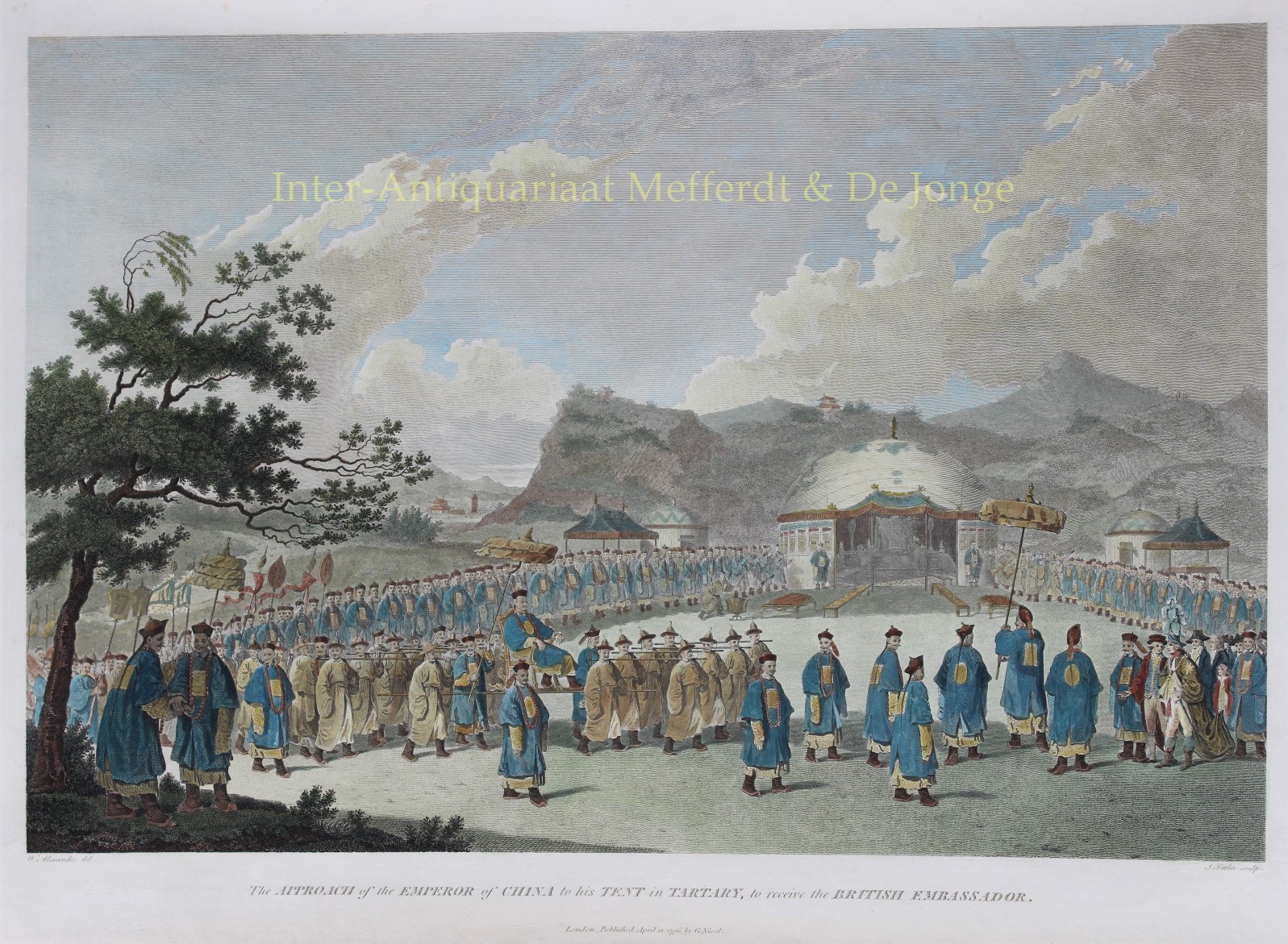

Meeting with the Chinese Emperor – after William Alexander, 1796

MEETING WITH THE EMPEROR AT CHENGDE (承德市) “The Approach of the Emperor of China to his Tent in Tartary, to…

Read more

MEETING WITH THE EMPEROR AT CHENGDE (承德市)

“The Approach of the Emperor of China to his Tent in Tartary, to receive the British Embassador.” Copper engraving by J. Fittler after a drawing by William Alexander (1767-1816 ) from the “Authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China; including cursory observations made, and information obtained, in travelling through that ancient empire” written by Sir George Leonard Staunton and published April 12, 1796 in London by G. Nicol. Coloured by a later hand. Size (image): 30 x 45 cm.

The embassy was headed by Earl George Macartney (1737-1806), who was dispatched to Beijing in 1792. He was accompanied by Staunton a medical doctor as his secretary, and a retinue of suitably impressive size, including Staunton’s 11-year-old son who was nominally the ambassador’s page. On the embassy’s arrival in China it emerged that the 11-year-old was the only European member of the embassy able to speak Mandarin, and thus the only one able to converse with the Emperor. Macartney was twice granted an audience with the Emperor and in December 1793 he was sumptuously entertained by the Chinese viceroy in Canton.

Lord Macartney’s embassy was unsuccessful, the Chinese resisting British overtures to establish diplomatic relations in view of opening the vast Chinese realms to free trade, but it opened the way for future British missions, which would eventually lead to the first Opium War and the cession of Hong Kong to Britain in 1842. It also resulted in this invaluable account, prepared at government expense, largely from Lord Macartney’s notes, by Staunton, of Chinese manners, customs and artifacts at the height of the Qing dynasty.

The engravings are of special interest because of their depiction of subjects that very few Europeans had heard of or seen, showing how advanced Chinese civilisation was on a technical, artistic and organizational level.

Staunton describes this particular engraving as follows: The tent of the Emperor “was erected for the purpose in a part of the grounds belonging to the palace and called Van-shoo-yuen, or garden of ten thousand trees. Before the tent were arranged in two ranks, a great number of persons, consisting of tributary princes representatives of sovereigns, ministers of state, governors of provinces, officers of the tribunals, and other mandarines of rank, waiting the approach of the Emperor, who is borne in an open chair supported by sixteen men. The British Embassador and his suite stood at the front of the rank, on the right hand side, in advancing towards the tent.”

Price: SOLD