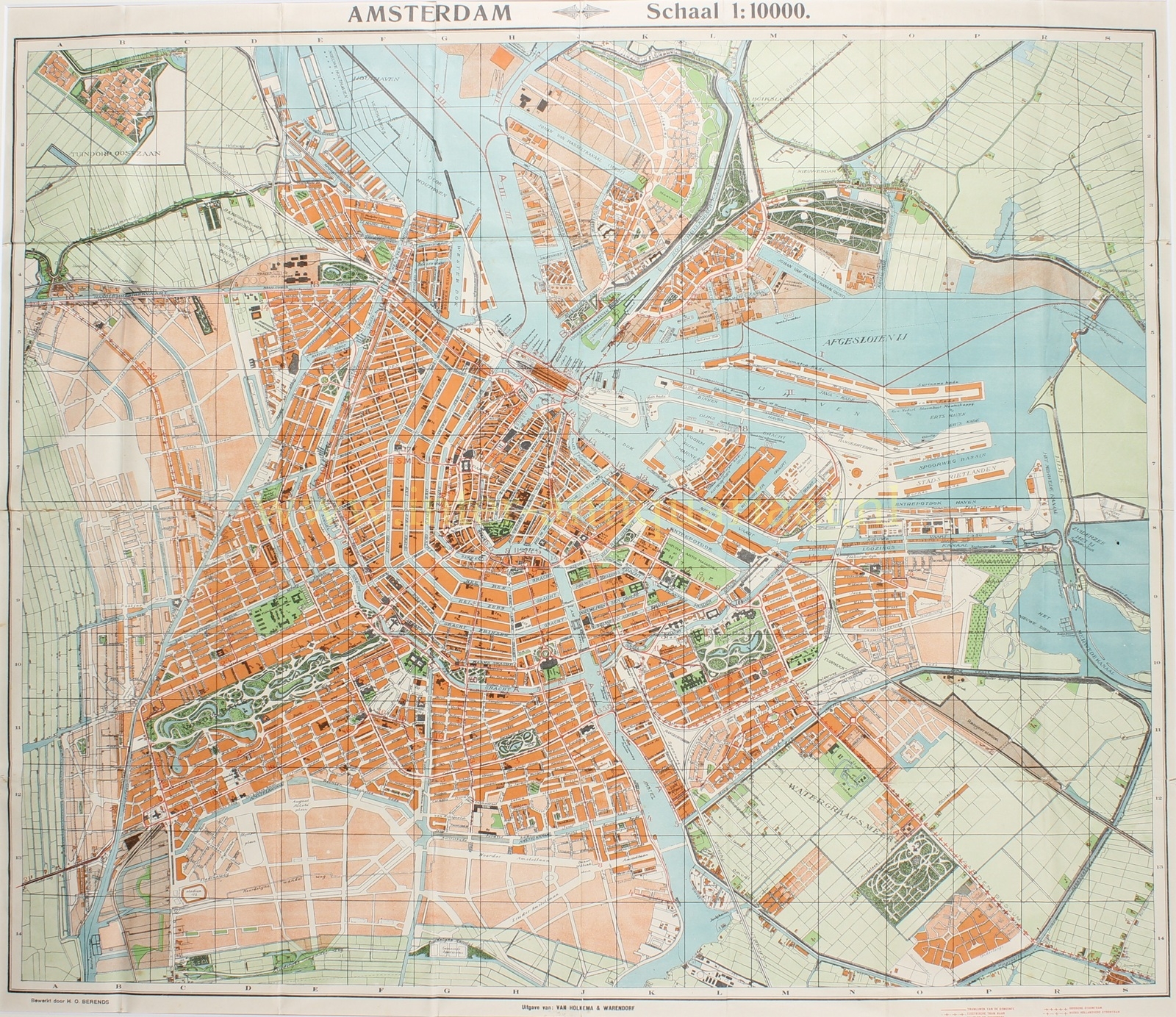

Amsterdam – H.O. Berends/Van Holkema & Warendorf, 1922-1923

“Amsterdam,” colour lithograph edited by H.O. Berends and published by Van Holkema & Warendorf in 1922-1923. Size (border) 65,5 x 73 cm.

The oldest known map of Amsterdam brought to the market by Tjomme van Holkema dates from 1882. After the 1892 merger into Van Holkema & Warendorf, the new firm issued a whole series of overview maps of the city. This example was printed in 1922–1923.

The built-up parts of the city are printed in orange, while the planned but not yet executed expansions are shown in light orange. The pastureland around Amsterdam is rendered in light green, and the parks within the city and the gardens outside it in dark green. The city’s main buildings are printed in flat, contrasting black. The harbour area, industrial sites, and the street grid are left in white.

By 1924, Amsterdam had just undergone a major territorial expansion. The annexations of 1921 had brought Watergraafsmeer, large parts of Amsterdam-Noord (including the former villages of Buiksloot, Nieuwendam, and Ransdorp), and lands in the west within the municipal boundary. These new neighborhoods are already included in this edition. The city still bordered the open Zuiderzee—the Afsluitdijk had yet to be constructed—and the North Sea Canal route determined the orientation of harbor and railway.

Dock work in the east was concentrated around the Oostelijke Handelskade and the islands of Java and KNSM; on the northern bank of the IJ, docks and shipyards are visible. In the west, new harbor areas were emerging, while within the city limits industrial complexes such as the Westergasfabriek and the railway yards around Centraal Station and Weesperpoort defined the urban landscape. Weesperpoort station was still in use; the map also shows Haarlemmermeer station (1914) as the southwestern railway terminus.

Housing developments followed the Housing Act and the architectural language of the Amsterdam School-style. In the west and north, new working-class neighborhoods were rising; in the east, the Indische Buurt was expanding and Watergraafsmeer was being parceled out. In the south, Berlage’s Plan Zuid is clearly drawn as a framework—boulevards, squares, and green spaces—but many of the definitive streets and building blocks were not yet in place. The Rivierenbuurt and Apollobuurt were just beginning their development.

Along Amstelveenseweg we still see the “Old Stadium” (officially “Het Nederlandsch Sportpark,” demolished in 1929). The Olympic Stadium would only be built a few years later.

Literature: Marc Hameleers (2003) “Amsterdamse Plattegronden 1866-2000”, no. 112.

Price: SOLD