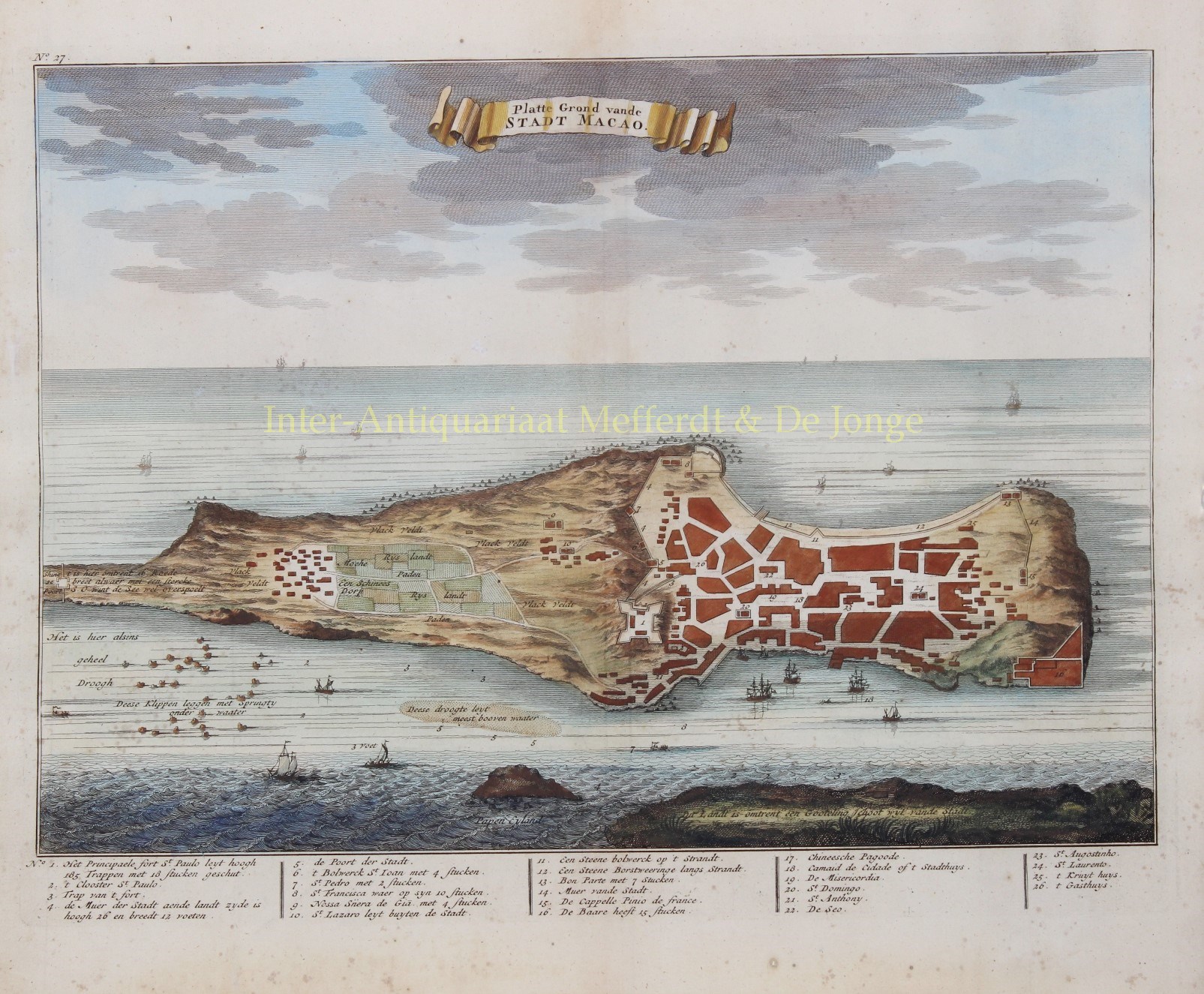

VIEW OF 17TH CENTURY MACAU

“Platte Grond vande Stadt Macao”. Copper engraving from François Valentyn’s “Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien”, engraved by Jan van Braam and published in Dordrecht by Gerard onder de Linden in 1724-1726. Coloured by a later hand. Size: 29 x 36 cm.

A fine view of the city of Macao from Lappa Island, extending to the Barrier Gate at the north of the promontory. European vessels and junks sail the surrounding waters.

After the Portuguese were allowed to permanently settle in Macau I 1557, both Chinese and Portuguese merchants flocked to Macau. It quickly became an important hub in the development of Portugal’s trade along three major routes: Macau–Malacca–Goa–Lisbon, Guangzhou–Macau–Nagasaki and Macau–Manila–Mexico. The Guangzhou–Macau–Nagasaki route was particularly profitable because the Portuguese acted as middlemen, shipping Chinese silks to Japan and Japanese silver to China, making significant profits in the process.

Macau’s golden age coincided with the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns, between 1580 and 1640. King Philip II of Spain was encouraged to not harm the status quo, to allow trade to continue between Portuguese Macau and Spanish Manila, and to not interfere with Portuguese trade with China.

The alliance of Portugal with Spain meant that Portuguese colonies became targets for the Netherlands, which was involved at the time in a lengthy struggle for its independence from Spain, in the Eighty Years’ War. After the Dutch East India Company was founded in 1602, the Dutch unsuccessfully attacked Macau several times.

As well as being an important trading post, Macau was a centre of activity for Catholic missionaries, as it was seen as a gateway for the conversion of the vast populations of China and Japan.

In 1685, the privileged position of the Portuguese in trade with China ended, following a decision by the Kangxi Emperor of China to allow trade with all foreign countries. Over the next century, England, the Dutch Republic, France, Denmark, Sweden, the United States and Russia moved in, establishing factories and offices in Guangzhou and Macau.

On the print, below the view, is an index showing the major buildings and fortresses, including Fort de Baare, Fortress of Our Lady of Bom Parto, Fort St Paulo [大炮台 – Monte Fort]. Churches and convents including, St. Layrentio, St. Angostino, de Seo [Cathedral], St. Dominic’s Church, St. Francisco, Cloister St. Paulo, St. Pedro, St. Joan, St. Antoni, St. Lazarus’ Church and Nossa Senora de Gia. Also indicated is the Shineesches Pagode [A-ma Temple].

François Valentyn was a prominent historian of the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.) who is best known for “Oud en Nieuw Oost Indiën”, his vast illustrated account of the Dutch trading empire in Asia. He travelled to the East Indies twice and served as Calvinist minister to Ambon between 1686 and 1694. In preparing this monumental work, he was given privileged access to the previously secret archives of the V.O.C., containing transcripts and copies of important earlier Dutch voyages.

While Valentyn’s maps and diagrams were prized possessions, his scholarship, judging by 21st century standards was unscrupulous. Valentyn’s use of the products of other scientists’ and writers’ intellectual labour and his passing it off as his own, reveals a penchant for self-aggrandisement.

Price: Euro 650,-