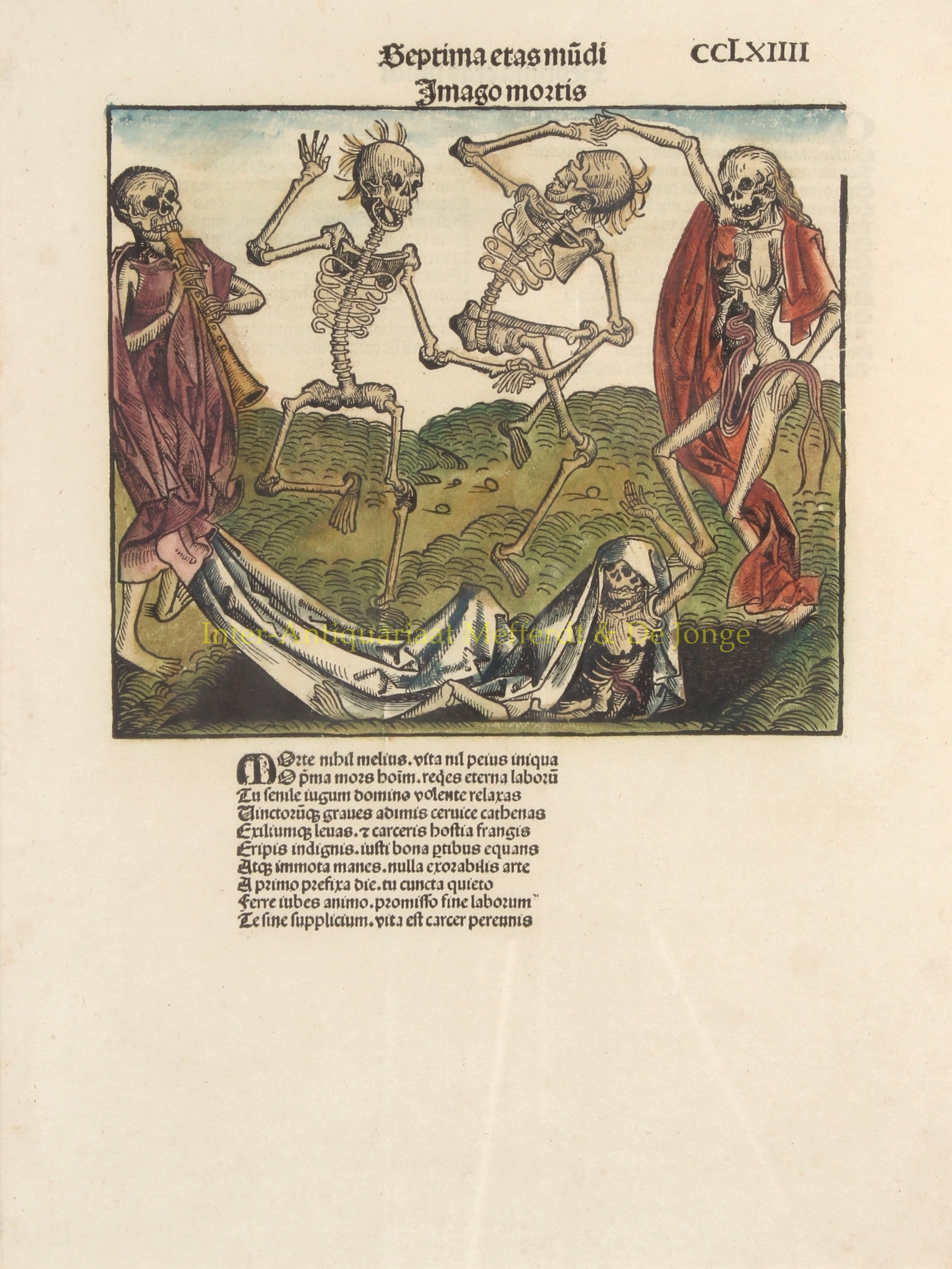

15TH CENTURY DANCE OF SKELETONS

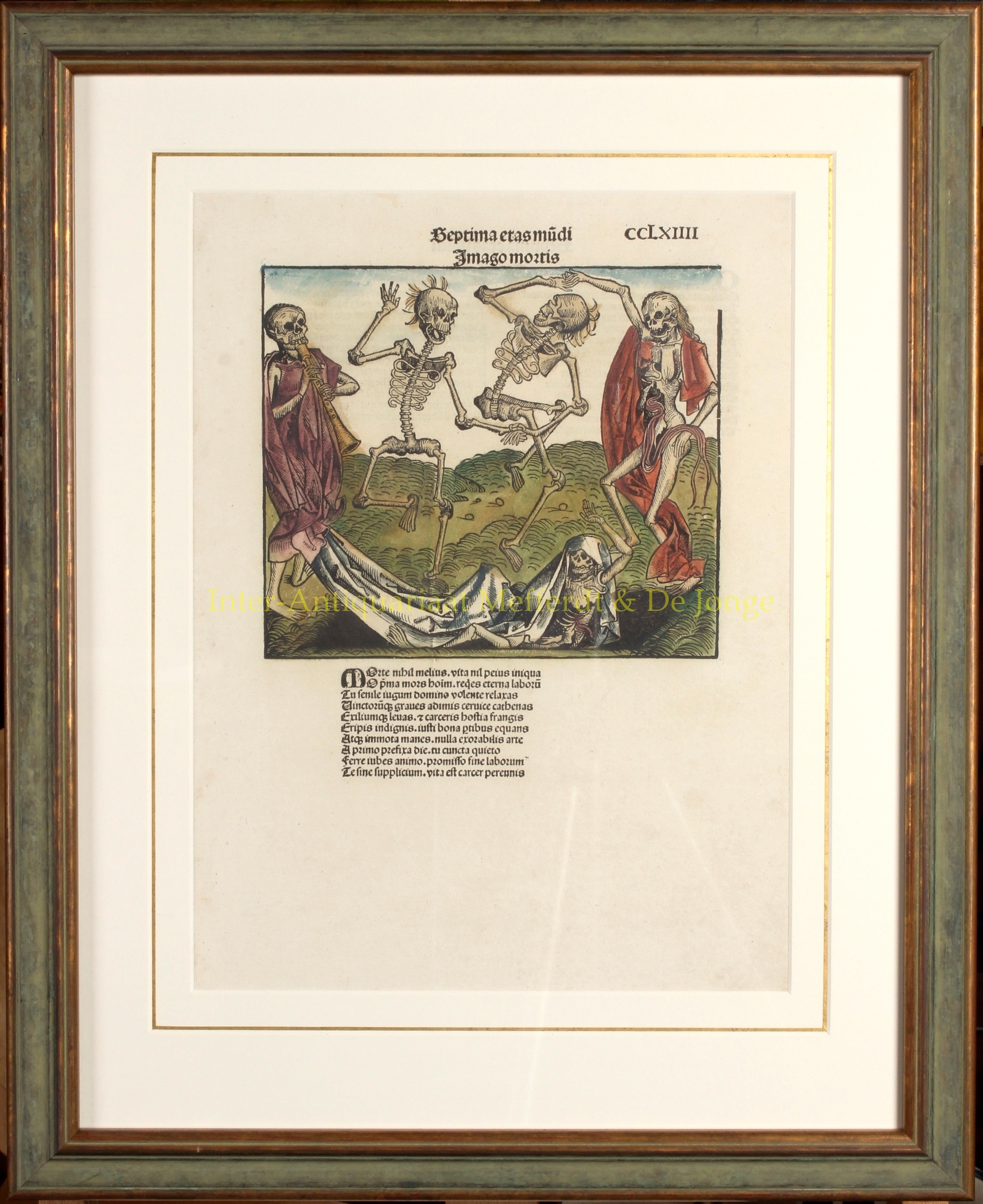

“Imago Mortis“, woodcut by Michael Wolgemut, for Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle published in 1493. With original hand colouring. Size (incl. text) 27 x 22,5 cm.

This is the famous, macabre scene from Schedel’s description of the Seventh Age (yet to come), or the reign of the Anti-Christ. The music for the frenzied Dance of Skeletons is provided by a horn player draped in a shroud. A skeleton rises from a grave, and the partially decomposed individual on the right joins the dance with his intestines casually draped over his arm.

The dance of skeletons is different from the dance of death or Danse Macabre in that it is strictly based on folklore, with no social or moral message. Skeletons are usually depicted coming forth from open graves, cavorting about, and often playing music and dancing. Wolgemut’s woodcut is a beautiful example of the genre, which was used to illustrate and thrill rather than educate or preach to the viewer.

Hartmann Schedel’s Liber Chronicarum: Das Buch der Croniken und Geschichten [book of chronicles and stories], popularly referred to as the Nuremberg Chronicle, based upon the city of its publication), was the first secular book to include the style of lavish illustrations previously reserved for Bibles and other liturgical works.

The project to produce the Nuremberg Chronicle was instigated by the artist Michael Wolgemut (1434/37-1519), who with Wilhelm Pleydenwurif (c. 1450-94), conceived and executed its illustrations and engravings (one of Wolgemut’s apprentices had included the young Albrecht Dürer but it is no longer thought that he worked on the Chronicle). To finance this expensive and hugely risky undertaking Wolgemut obtained the support of two wealthy patrons, Sebald Schreyer (1446-1520) and his brother-in-law Sebastian Kammermaister (1446-1520), after which the famous Nuremberg printer Anton Koberger (ca.1440-1513), agreed to do the printing. The task of actually writing the work was assigned to the Nuremberg physician and humanist Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514). The diverse range of medieval and Renaissance sources used were drawn from authors Schedel studied as a student (at Leipzig and Padua), including Bede, Vincent of Beauvais, Martin of Tropau, Flavius Blondus, Bartolomeo Platina and Philippus de Bergamo. Like most incunabula (i.e. books printed before 1501), the work was published in Latin, although a German version was also produced a few months later, which was quickly followed by further pirated editions .

The work was intended as a history of the world, from beginning of time to the 1490s, with a final section devoted to the anticipated Last Days of the World. It is without question the most important illustrated secular work of the 15th Century and its importance rivals the early printed editions of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia and Bernard von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam in terms of its importance in the development and dissemination of illustrated books in the 15th Century.

While the majority of the illustrations in the book depict the various saints, royalty, nobles and clergyman of the period, the work is perhaps best known for the large format views of a number of the major European Cities, including Rome, Venice, Paris, Vienna, Florence, Genoa, Saltzburg, Cracow, Breslau, Budapest, Prague, and major cities in the Middle East, including Jerusalem, Alexandria, Constantinople, as well as a number of cities in what would become the German Empire.

The work also included a magnificent double page map of the World, a large map of Europe and several famous illustrations, including this dance of skeletons, and scenes from the Creation and the Last Judgement. While many of the double-page city views are less than accurate illustrations of the cities as they existed at the end of the 15th Century, they are of great importance in the iconographic history of each of the cities depicted.

Price: SOLD