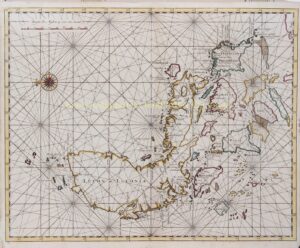

EARLIEST OBTAINABLE LARGE CHART OF THE PHILIPPINES

“Lucon of Luconia” Copper engraving from François Valentijn’s “Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indien”, made by Jan van Braam and published in Dordrecht by Gerard onder de Linden in 1724-1726. Coloured by a later hand. Size: 30,8 x 38,8 cm.

Oriented with east at the top, Valentijn’s chart map encompasses Luzon and its associated islands to the immediate south. The chart is filled with rhumb lines, with one decorative compass rose in the waters north of the islands. Sounding depths are included near shore, as are sand banks, shoals, and obstructions. A scale is in the upper left corner. Port cities are also included.

Luzon is the main focus of this chart, an appropriate emphasis as it is the largest island in the Philippines archipelago and the most populous. It also contains one of the most important ports in the entire Pacific, Manila, which was part of a cross-oceanic trade route linking Acapulco in New Spain to Manila and the markets of Asia.

Luzon has always maintained strong trading and exchange ties with neighbouring islands groups and mainland Asia. The explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in 1521 and nominally claimed the islands for Spain. However, the Spanish exercised no real control until 1565, when Miguel López de Legazpi began the first Spanish settlements near Cebu, here the island is called “Celo.” The Spanish declared Manila the capital in 1571. When this chart was made, the islands were still under Spanish control, as they would be until 1898.

François Valentijn was a prominent historian of the Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.) who is best known for “Oud en Nieuw Oost Indiën”, his vast illustrated account of the Dutch trading empire in Asia. He travelled to the East Indies twice and served as Calvinist minister to Ambon between 1686 and 1694. In preparing this monumental work, he was given privileged access to the previously secret archives of the V.O.C., containing transcripts and copies of important earlier Dutch voyages.

While Valentijn’s maps and diagrams were prized possessions, his scholarship, judging by 21st century standards was unscrupulous. Valentijn’s use of the products of other scientists’ and writers’ intellectual labour and his passing it off as his own, reveals a penchant for self-aggrandisement.

Price:SOLD