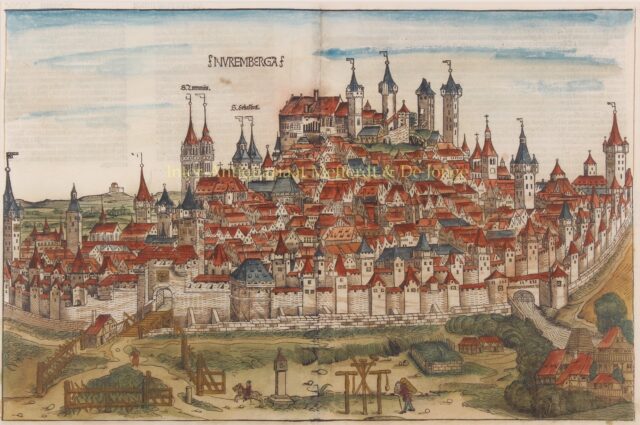

Neurenberg (Nürnberg) – Hartmann Schedel, 1493

NUREMBERG AT ITS HEYDAY “Nuremberga”, woodcut from a Latin edition of the famous “Liber chronicarum” by Hartmann Schedel, printed by…

Lees verder

NUREMBERG AT ITS HEYDAY

“Nuremberga”, woodcut from a Latin edition of the famous “Liber chronicarum” by Hartmann Schedel, printed by Anton Koberger in 1493. With beautiful original 15th-century hand colouring. Size:34 x 52,5 cm.

The Imperial City of Nuremberg (German: “Reichsstadt Nürnberg”) was a free imperial city — independent city-state — within the Holy Roman Empire. After Nuremberg gained piecemeal independence from the Burgraviate of Nuremberg in the High Middle Ages and considerable territory from Bavaria in the Landshut War of Succession, it grew to become one of the largest and most important Imperial cities, the unofficial capital of the German Empire.

The cultural flowering of Nuremberg, starting in the 15th century, made it the centre of the German Renaissance. Nuremberg traded in virtually all of the then-known world and its wealth was known as ‘the Imperial Treasure Chest’. The city’s revenues were said to have been greater than those of the whole kingdom of Bohemia. Nuremberg maintained trade offices in many cities, such as the Nürnberger Hof in Frankfurt.

At that time, many notable artists lived and worked in Nuremberg, such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Martin Behaim (1459–1507) built the first globe and Peter Henlein (c. 1485–1542) produced the first pocket watch. Also notable from this period are the woodcarver Veit Stoss (1447–1533), the sculptor Adam Kraft (c. 1460–1508/09) and the master founder and sculptor Peter Vischer the Elder (c. 1460–1529).

Hartmann Schedel’s Liber Chronicarum: Das Buch der Croniken und Geschichten [book of chronicles and stories], popularly referred to as the Nuremberg Chronicle (from the city of its publication), was the first secular book to include the style of lavish illustrations previously reserved for Bibles and other liturgical works.

The project to produce the Nuremberg Chronicle was instigated by the artist Michael Wolgemut (1434/37–1519), who with Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (c. 1450-94), conceived and executed its illustrations and engravings (one of Wolgemut’s apprentices included the young Albrecht Dürer but it is no longer thought that he worked on the Chronicle). To finance this expensive and hugely risky undertaking Wolgemut obtained the support of two wealthy patrons, Sebald Schreyer (1446-1520) and his brother-in-law Sebastian Kammermaister (1446-1520), after which the famous Nuremberg printer Anton Koberger (ca.1440-1513), agreed to do the printing.

The task of actually writing the work was assigned to the Nuremberg physician and humanist Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514). The diverse range of medieval and Renaissance sources used were drawn from authors Schedel studied as a student (at Leipzig and Padua), including Bede, Vincent of Beauvais, Martin of Tropau, Flavius Blondus, Bartolomeo Platina and Philippus de Bergamo. Like most incunabula (i.e. books printed before 1501), the work was published in Latin, although a German version was also produced a few months later.

The work was intended as a history of the world, from beginning of time to the 1490s, with a final section devoted to the anticipated Last Days of the World. It is without question the most important illustrated secular work of the 15th Century and its importance rivals the early printed editions of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia and Bernard von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam in terms of its importance in the development and dissemination of illustrated books in the 15th Century.

The depiction of Nuremberg is the only two-page, text-free spread of a town in the book. Clearly, not all town views were accurately portrayed, but Nuremberg’s importance as an imperial city, with a vibrant merchant and intellectual class, was realistically shown, from the labelled spires of the churches of St. Sebaldus and St. Lorenz to the many other architectural features such as the castle (one of Europe’s most formidable medieval fortifications), towers, city gate, and bridge, as well as the paper mill in the bottom right corner.

Price: SOLD