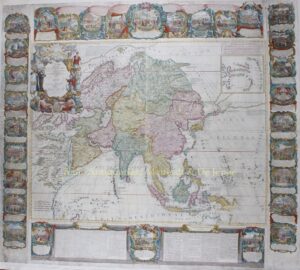

Asia – Jean-Baptiste Crépy + Jean-Baptiste Nolin, 1781

€14.500

RARE AND MONUMENTAL WALL MAP OF ASIA

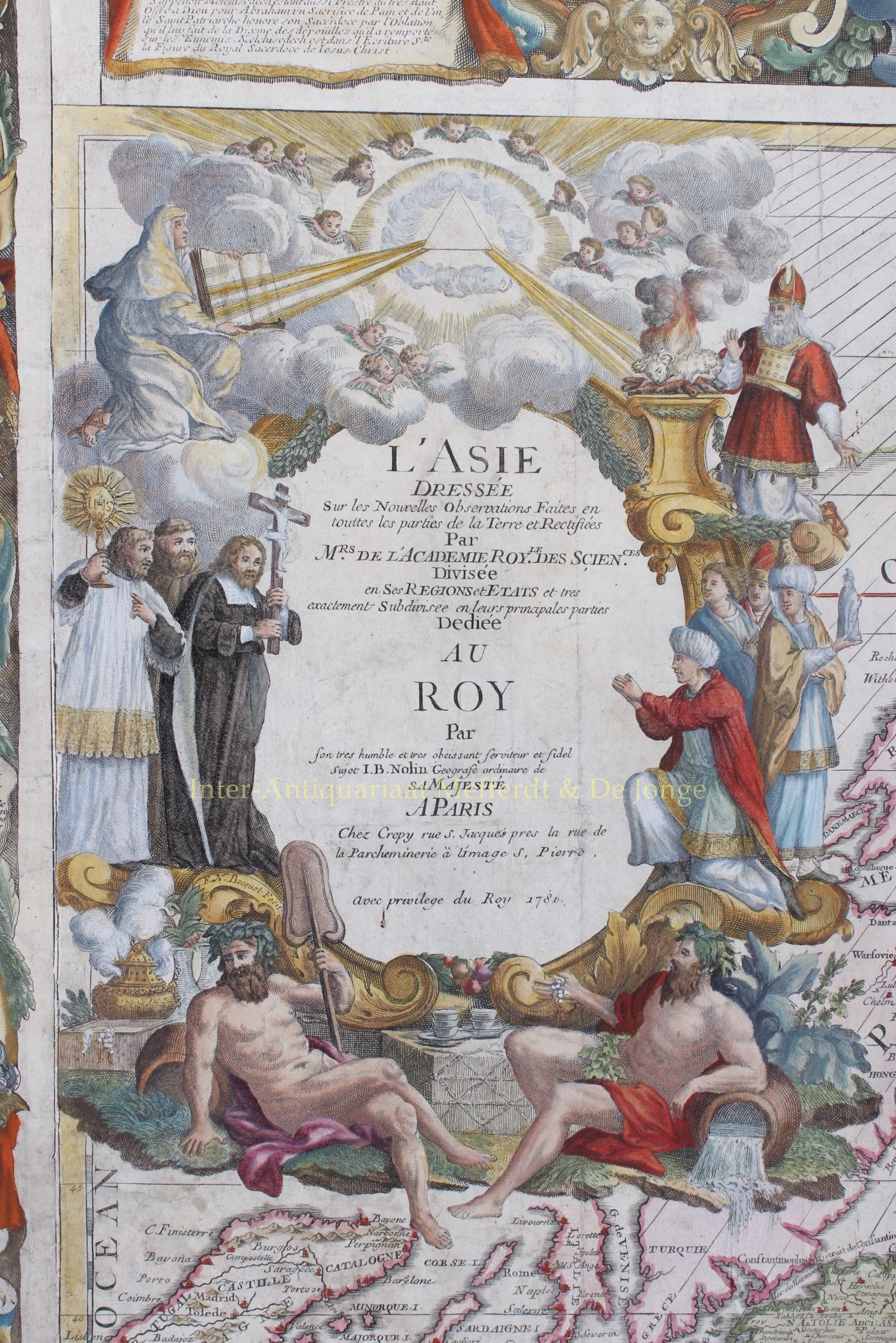

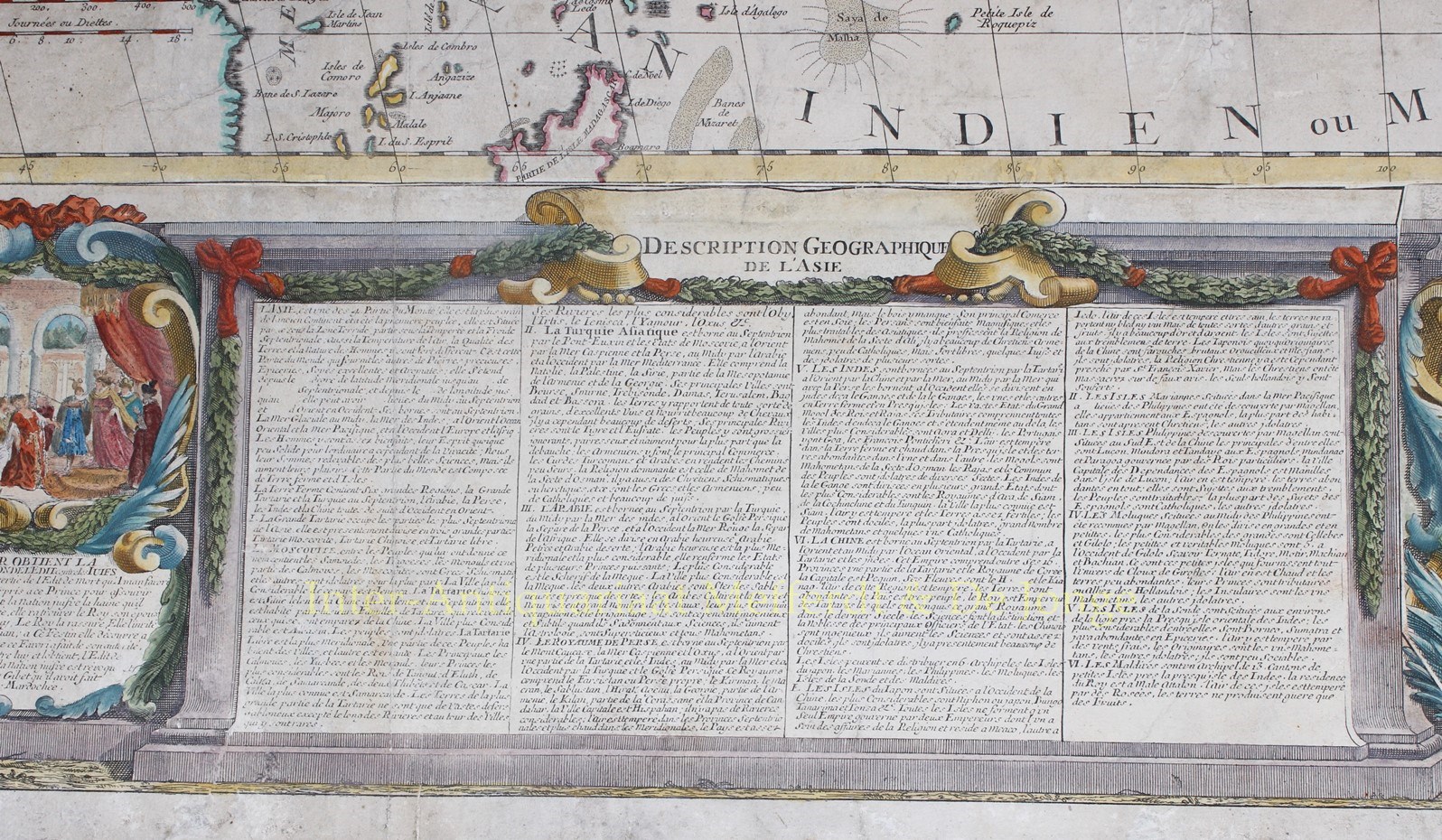

“L’Asie dressée sur les nouvelles observations faites en touttes [sic] les parties de la terre et rectifiées.” Copper engraving by Jean-Baptiste Nolin, published in Paris by Jean-Baptiste Crépy in 1781 on 4 central sheets, plus borders. Mounted on linen. Size: approx. 126 x 140 cm.

Nolin’s map was produced at the junction of the decline of the Dutch dominance of world exploration and cartography and the rise of the British and French. The map consequently provides a fitting bridge between the two eras.

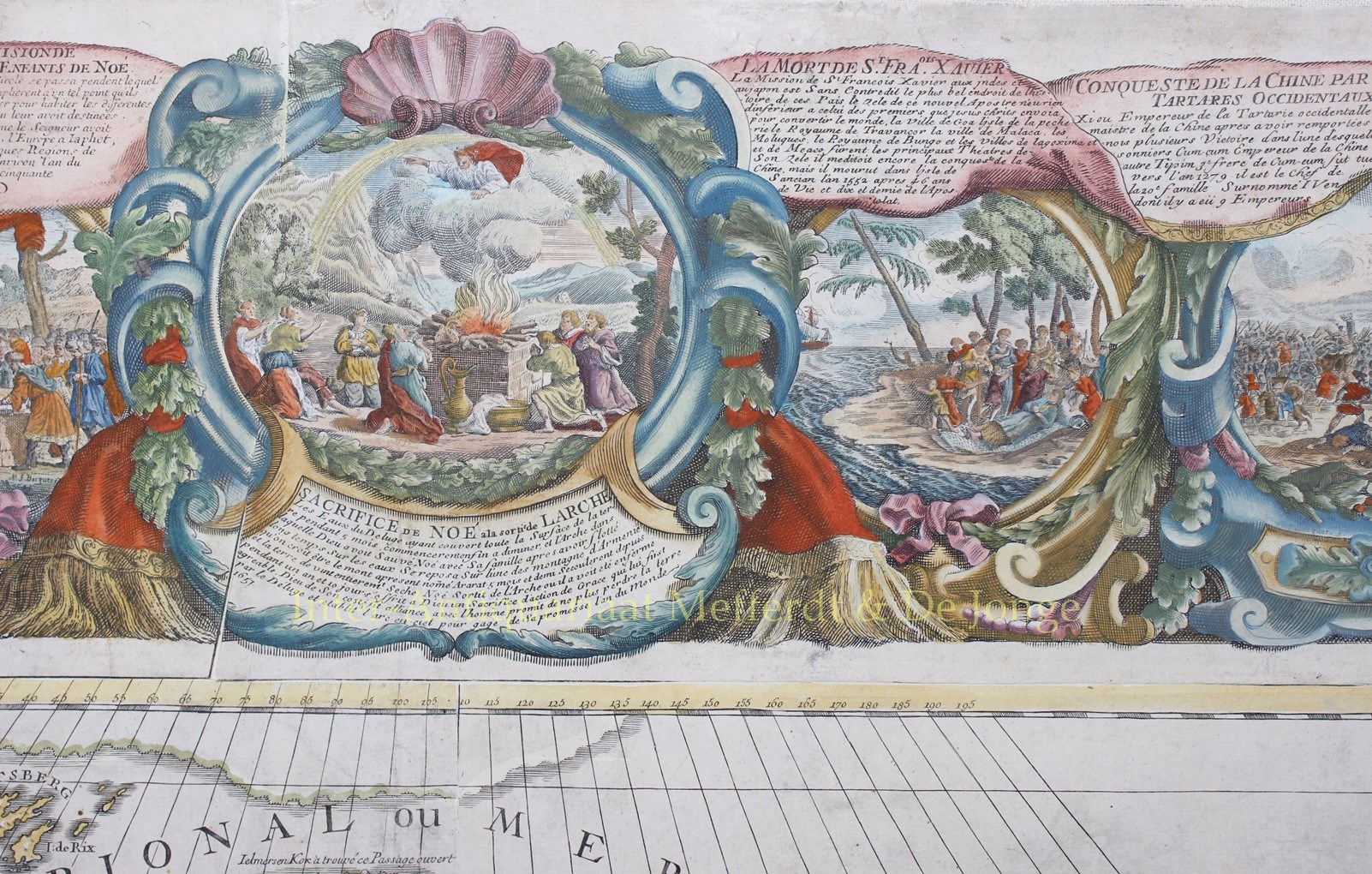

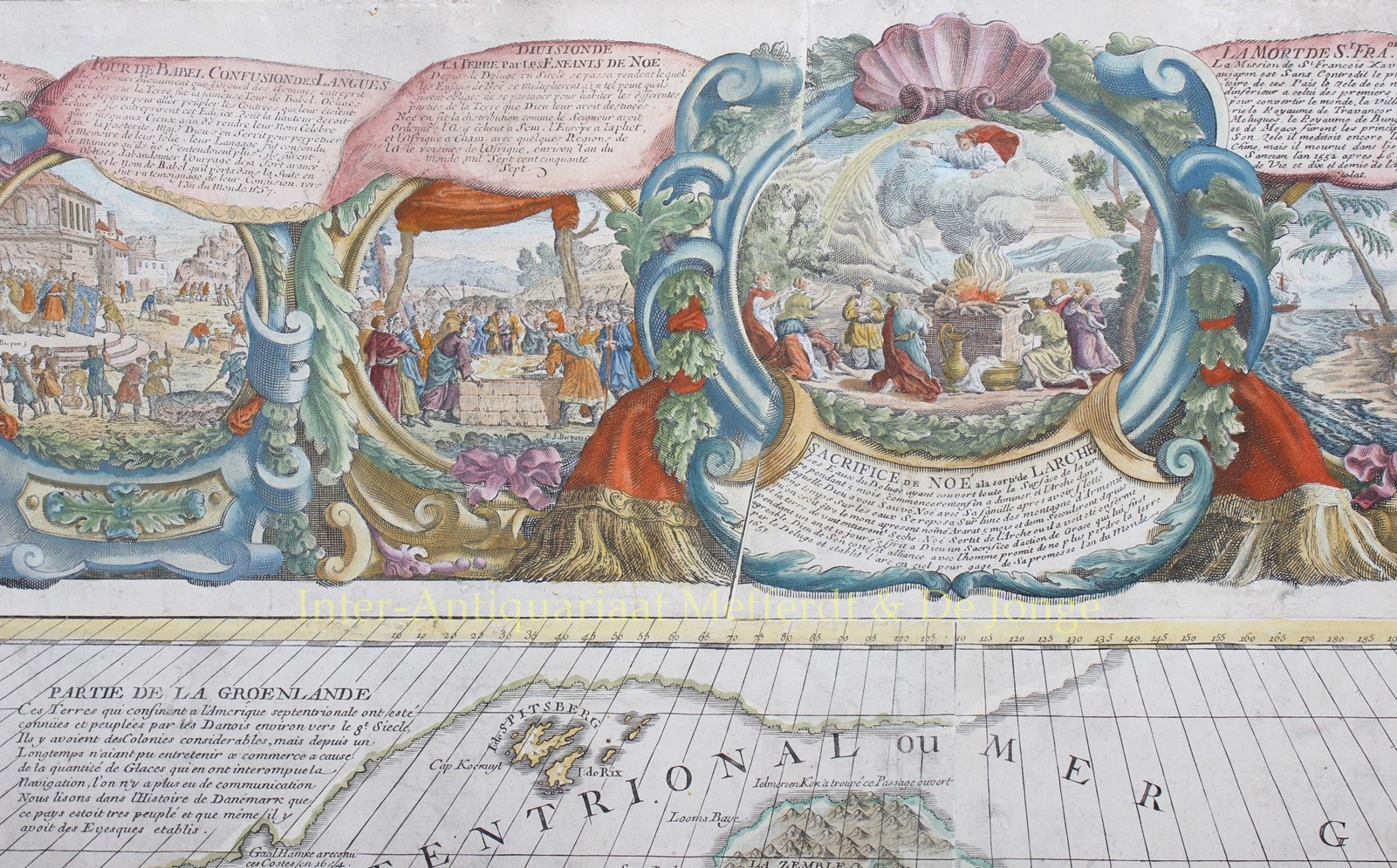

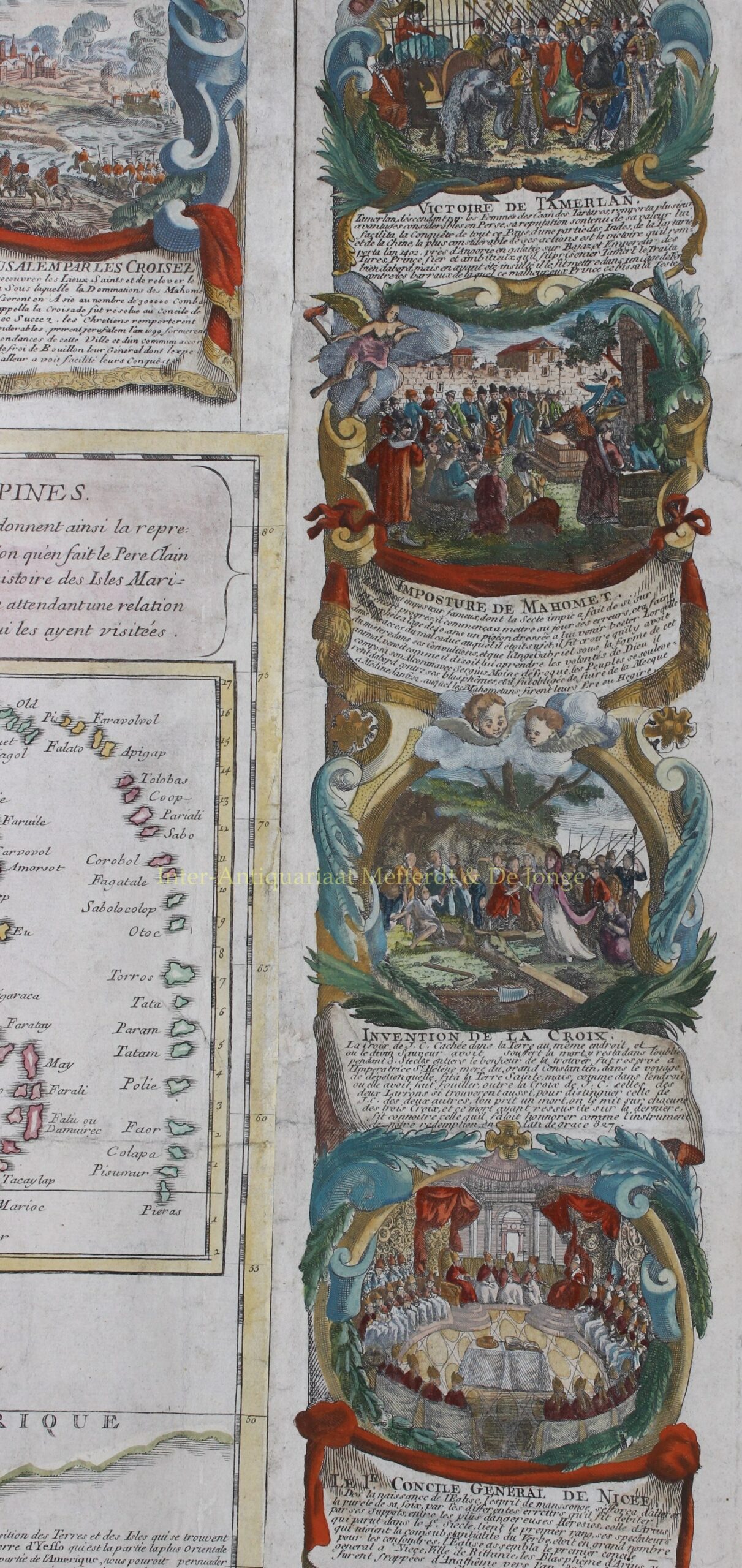

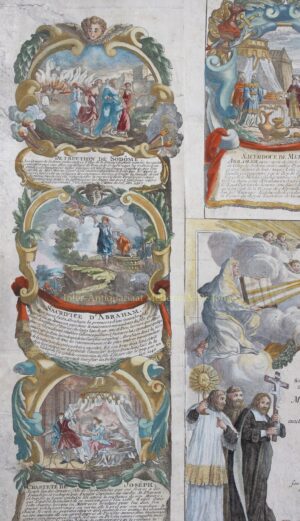

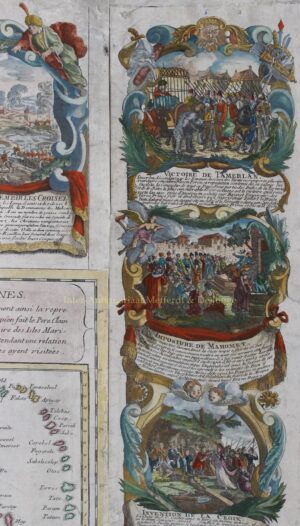

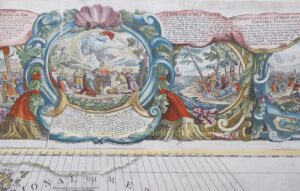

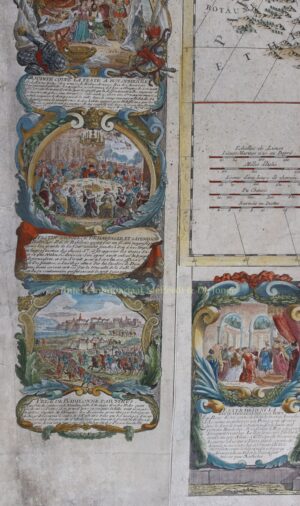

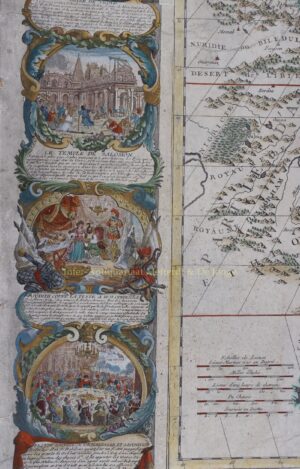

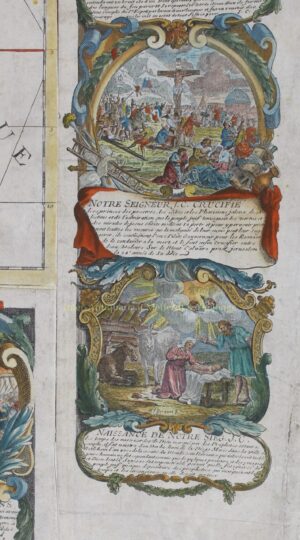

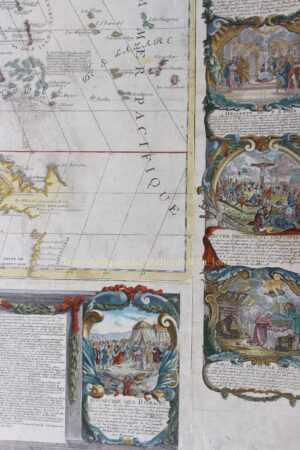

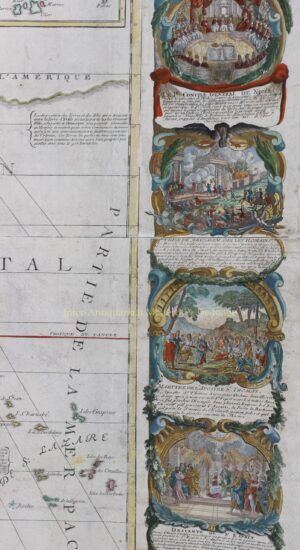

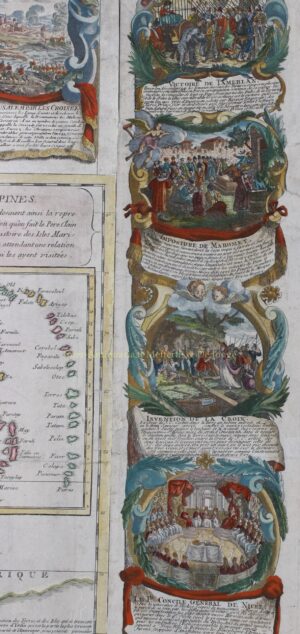

Geographically, the map features the Asian continent, including an allegorical cartouche, a geographical and a historical description in the lower decorative border, and 30 vignettes on Asian history rendering an interesting mix of biblical history of Asia Minor, the Tartarian invasion of China, the Crusades with the Sieges of Damietta and Jerusalem etc.Cartographically the map is based upon the work of Nolin’s father of the same name. It extends from the Mediterranean to New Guinea and the Japanese Kuril Islands, and from Spitzbergen to Northern Australia.

The map is surrounded by elaborate decorative imagery including 30 decorative vignette medallions drawn from Greek, Roman, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic history. The extensive text along the lower margin features a Description Géographique de l’Asie and a Description Historique de l’Asie. In the upper left corner, an especially resplendent cartouche illustrates Jesuit priests evangelizing to the diverse peoples of the continent.

While exhibiting extensive confidence and detail throughout, this map is heavily speculative with regards to unexplored territory. Greenland for example, extends eastward north of Spitsbergen almost as far as Nova Zembla, which itself is attached to the Asiatic mainland. India is exceptionally narrow following Nicolas Sanson’s model of around 1690.

The sea between Japan and Korea, whose name, nowadays either the “Sea of Korea”, “east Sea”, or the “Sea of Japan”, is currently a matter of historical and political dispute between the countries and is here identified in favor of both countries, with both Mer et Golfe de Coree and Mer Septentrionale du Japon applied to the same sea.

The map’s most speculative sections are in East and Northeast Asia, where, despite being issued after the explorations of Vitus Bering, the cartography here dates to about 1740, due to the fact that Bering’s information was not yet widely available outside of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Instead, the cartographer relies on early Dutch records relating to the voyage of Maarten Gerrtisz de Vries and Cornelis Jansz Coen. Here modern day Hokkaido (“Terre d’Yesso“), the southern parts of which are vaguely recognizable, is attached to the Yupi peninsula (Sakhalin). Several islands extending to the northeast, represent De Vries and Coen’s discovery of the Japanese Kuril Islands of Kunashir (mapped somewhat accurately) and Iturup. De Vries and Coen’s mapping of Iturup does not extend beyond the western shores, so the eastern part of the island remains blank. Some cartographers of the period attached Iturup to a larger land maps identified as “Terre de Gama”. Gama, in this case refers to the Portuguese explorer João da Gama (c. 1540 – after 1591), grandson of Vasco de Gama, who reportedly crossed the North Pacific in the 1580s, in the process mapping some of the Kuril Islands, possibly some of the Aleutian Islands, and potentially even part of the American Coast. ‘Gamaland’ was subsequently mapped speculatively on many maps. The reality of Gamaland, as presented here by Nolin, is probably a mismapping of several of the Aleutian Islands as a single landmass attached to the American mainland. Here that landmass, identified as “Partie de L’Amerique” is ghosted in suggested a tenuous state of discovery.

Just to the north of these islands the Amur River (Yaniour) exhibits a particularly fiery and virulent outflow into the Arctic – suggesting impassibility. The Amur river was explored by the Russian Cossack expedition of Vassili Poyarkov in 1643–44. The Cossacks established the fort of Albazin on the upper Amur, mapped here, at the site of the former capital of the Solon people. When this map was issued, the fort has fallen under the control of the Chinese.

Further to the north there is an unusual projection into the Arctic generally known as Witsen’s Peninsula. This oddity appears on numerous maps dating from the late 17th and early 19th century. It is a legacy of Peter the Great‘s obsession over the search for a Northeast Passage. Around 1648 the Cossack Semyon Dezhnev (1605 – 1673) put together a rough and ready expedition to explore the region. His company consisted of Fedot Alekseyev, traveling with the merchants Andreev and Afstaf’iev (representing the Guselnikov merchant house), who provided their own ship, and Gerasim Ankudinov, an experienced sea captain with his own ship and some 30 men. Dezhnev, along with Mikhail Stadukhin, recruited some 19 men of their own and procured a traditional koch ship. Including escort vessels, a total seven ships sailed from the mouth the Kolyma River, along the Siberian Arctic, to the Anadyr River north of Kamchatka, and in doing so became the first Europeans to sail through the Bering Strait some 80 years before Vitus Bering. Dezhnyov described rounding a large mountainous promontory identified as Chukchi Peninsula. Of the seven vessels the multiple leaders, only three ships, including Dezhnev’s, survived the passage. His expedition was mostly forgotten outside of limited cartographic circles until Gerhardt Friedrich Müller discovered Dezhnyov’s reports and in 1758 published them. Dezhnyov ultimately proved that there was indeed a nautical route from Russia to East Asia, but at the same time confirmed that it was exceedingly impractical for trade. Nonetheless, his promontory was subsequently embraced by European cartographers who, lacking serious scientific data from the Dezhnyov expedition, surmised the form. The first of these was Dutchman Nicholaes Witsen, who prepared a map in 1687 based upon Dezhnyov’s records that he discovered on a 1665 trip to Moscow – hence the term Witsen’s Peninsula. Many cartographers followed suit, and some, like Nolin here, even went so far as to suggest that this landmass may actually be connected to America. Curiously, in doing so, Nolin both embraces and dismisses Dezhnyov, whose journey provided the first definitive proof that Asia was not connected to America.

Nolin maps the apocryphal Lake Chiamay roughly in what is today Assam, India. Early cartographers postulated that such a lake must exist to source the four important Southeast Asian river systems: the Irrawaddy, the Dharla, the Chao Phraya, and the Brahmaputra. This lake began to appear in maps of Asia as early as the 16th century and persisted well into the mid-18th century. Its origins are unknown but may originate in a lost 16th century geography prepared by the Portuguese scholar Jaõ de Barros. It was also heavily discussed in the journals of Sven Hedin, who believed it to be associated with Indian legend that a sacred lake linked several of the holy subcontinent river systems. There are even records that the King of Siam led an invasionary force to take control of the lake in the 16th century. Nonetheless, the theory of Lake Chiamay was ultimately disproved and it disappeared from maps entirely by the 1760s.

The Caspian Sea features two large whirlpools. These illustrations are possibly the earliest representation of factual cyclonic whirlpools that appears in Middle and South Caspian waters due to the massive inland sea’s unique current.

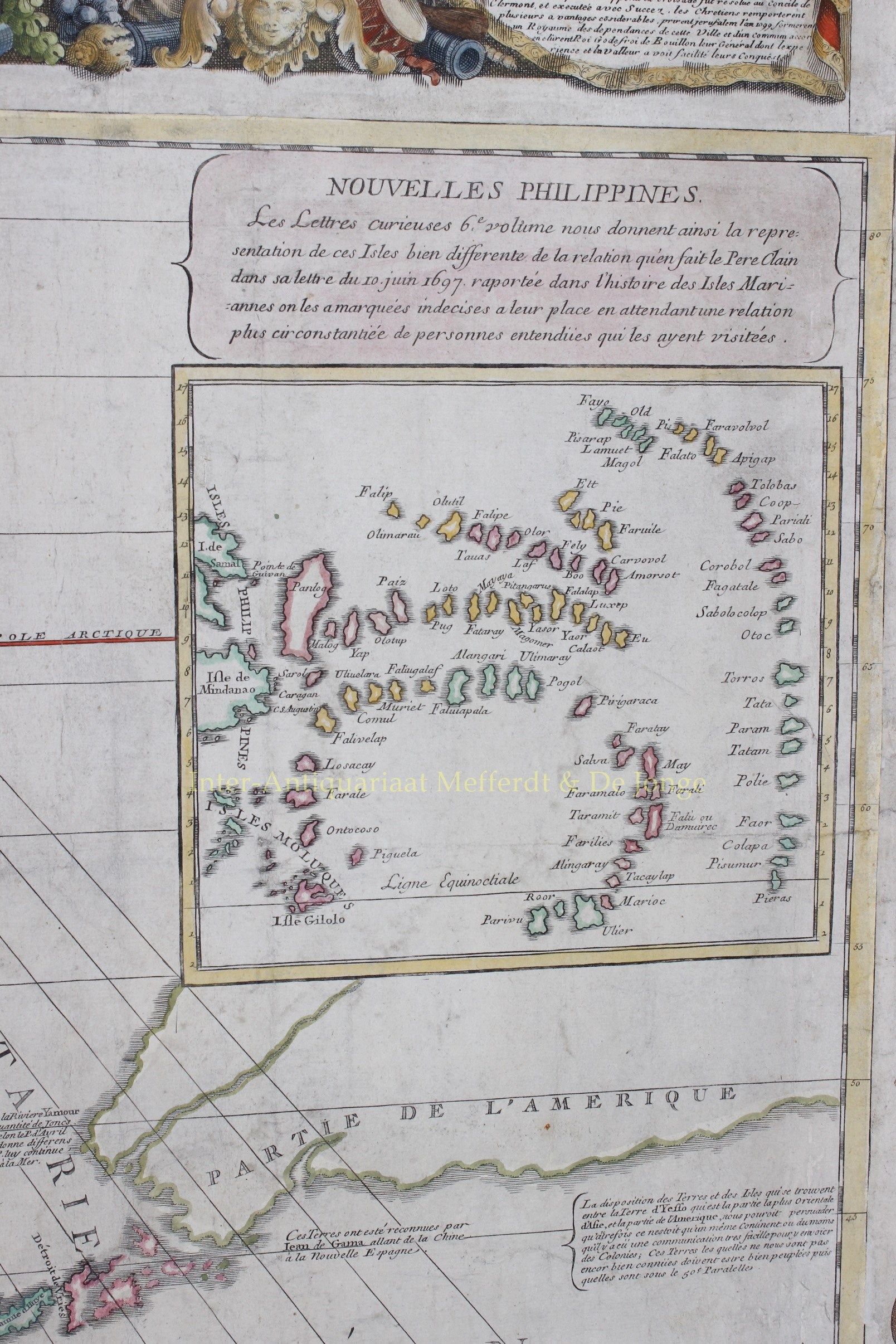

In the upper right corner of the map there is an inset mapping of the “Nouvelle Philippines” based upon a Jesuit report of 1697. These are better known as the Mariana Islands, also called the Isles des Larrons, an archipelago to the southeast of the Philippines. Curiously, the Mariana Islands are also mapped on the main chart according to the more accurate reports of Jesuit explorer Paulus Klein, the provincial superior of the Jesuit order in the Philippines from 1708-1712. The curious double mapping may suggest either that Nolin was unsure of the true geography of these islands or that he thought they may in fact be separate archipelagos.

On the whole, this map offers much of interest and withstands extensive perusal with an almost endless array of cartographic delights. The map is one of the greatest subjects of the Nolins’ legacy, not only being a masterful work of art and a fascinating image that tests the very limits of European geographical knowledge, but a vivid record of a dramatic transitional period in the history of cartography, and of society in general.

Price: Euro 14.500,-