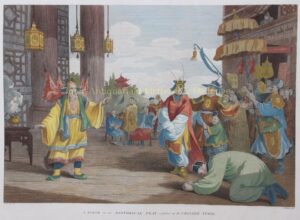

Chinese theatre – after William Alexander, 1796

“A scene in an historical play exhibited on the Chinese Stage.” Copper engraving by James Heath after a drawing by William Alexander (1767-1816 ) from the “Authentic account of an embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China; including cursory observations made, and information obtained, in travelling through that ancient empire” written by Sir George Leonard Staunton and published April 12, 1796 in London by G. Nicol. Coloured by a later hand. Size (image): 24 x 35,3 cm.

The embassy was headed by Earl George Macartney (1737-1806), who was dispatched to Beijing in 1792. He was accompanied by Staunton a medical doctor as his secretary, and a retinue of suitably impressive size, including Staunton’s 11-year-old son who was nominally the ambassador’s page. On the embassy’s arrival in China it emerged that the 11-year-old was the only European member of the embassy able to speak Mandarin, and thus the only one able to converse with the Emperor.

Lord Macartney’s embassy was unsuccessful, the Chinese resisting British overtures to establish diplomatic relations in view of opening the vast Chinese realms to free trade, but it opened the way for future British missions, which would eventually lead to the first Opium War and the cession of Hong Kong to Britain in 1842. It also resulted in this invaluable account, prepared at government expense, largely from Lord Macartney’s notes, by Staunton, of Chinese manners, customs and artifacts at the height of the Qing dynasty.

The engravings are of special interest because of their depiction of subjects that very few Europeans had heard of or seen, showing how advanced Chinese civilisation was on a technical, artistic and organizational level.

This particular print is one of the principal scenes from a drama the Europeans had seen: “One of the dramas, particularly, attracted the attention of those who recollected scenes, somewhat similar, upon the English stage. The piece represented an emperor of China and his empress living in supreme felicity, when, on a sudden, his subjects revolt, a civil war ensues, battles are fought, and at last the archrebel, who was a general of cavalry, overcomes his sovereign, kills him with his own hand, and routes the imperial army. The captive empress then appears upon the stage in all the agonies of despair naturally resulting from the loss of her husband and of her dignity, as well as the apprehension for that of her honour. Whilst she is tearing her hair and rending the skies with her complaints, the conqueror enters, approaches her with respect, addresses her in a gentle tone, soothes her sorrows with his compassion, talks of love and adoration, and like Richard the Third, with lady Anne, in Shakspeare, prevails, in less than half an hour, on the Chinese princess to dry up her tears, to forget her deceased consort, and yield to a consoling wooer. The piece concludes with the nuptials, and a grand procession.” One of the principal scenes is represented in Plate 30 of the folio volume.

Price: SOLD