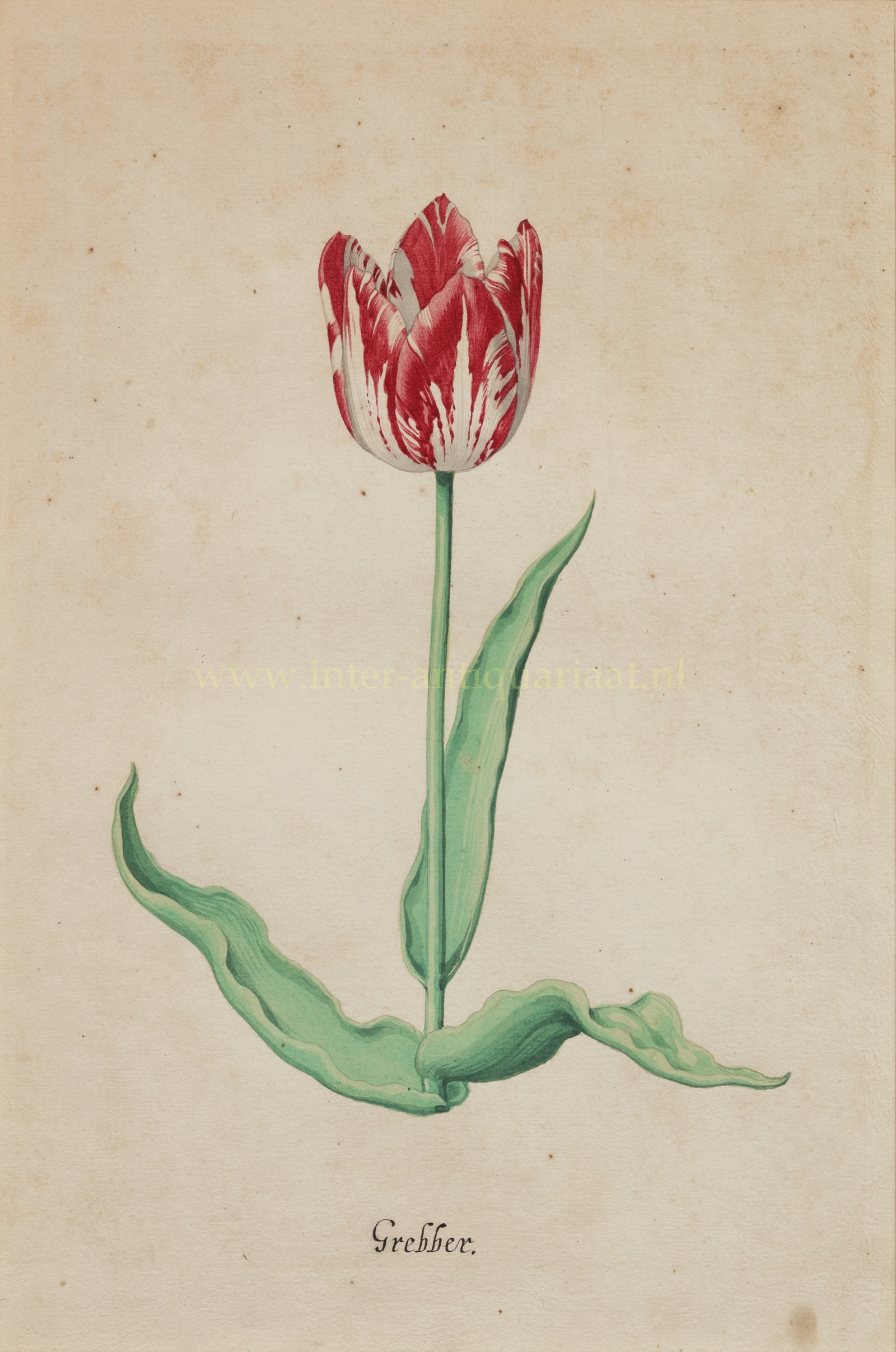

Tulip – Pieter Holsteyn II, c. 1645

€9.750

RED-WHITE ‘BROKEN’ TULIP

“Grebber” drawing in pen and gouachemade by Pieter Holsteyn II around 1645. Size (paper): 29,2 x 19,4 cm. (Frame: 48,5 x 38,5 cm.)

In the early 16th century, botany was a fledgling science. No one knew what caused the streaked and wild coloration of the most coveted tulips. One thing was certain: these flowers could commanded prices as high as the cost of a grand house on one of Amsterdam’s main canals.

Love and greed for these spectacular flowers inspired collectors and breeders to perform all kinds of experiments, hoping to uncover how produce multi-coloured blooms from single coloured tulips. They applied strange concoctions to planting beds or individual bulbs—pigeon dung, old plaster, manure, dishwater, even powdered paint. Tulip bulbs were exposed to the elements, planted in poor soil, soil imported from distant lands, or beds where broken flowers had bloomed before. Some bulbs were planted too deeply or in too little earth, but little seemed to guarantee a break.

Breeders came closest to success when they bound bulbs of broken and unbroken tulips together, generally to the detriment of each, but very occasionally a survivor of this process would break into the coveted flames.

Broken bulbs did produce identical plants through offsets, but the plants were often reproduced at a slower rate than single colour flowers. The difficulty of propagating broken bulbs significantly increased the perceived value of the flamed beauties.

In 1928, British mycologist Dorothy Cayley discovered that an aphid-borne disease caused breaking in tulips. In the 1960s, the disease was identified as tulip breaking virus (TBV). The virus causes a mixture of fading and excess pigmentation on the surfaces of each petal of a tulip flower.

Exact symptoms can vary slightly from tulip to tulip. Different strains of the virus can cause different symptoms, as well as other factors like the time of infection. However, once a bulb is infected, all of its offshoots will be as well. The virus also causes a gradual weakening of the bulb, reducing the number and strength of offsets. Over time, a broken tulip is more likely to die out than to multiply. This is why the old patterns of broken tulips like the “Grebber” disappeared long ago.

Once the cause of breaking was known, and the ill effects of the virus confirmed, breeders recognized that broken flowers posed a threat to the health of their tulip beds. The virus spreads easily and can threaten healthy cultivars. Commercial tulip growers began to weed out and destroy the kinds of flowers that had once been valued above all others. Today, very few breeders raise broken tulips of any kind, and planting broken tulips is illegal in the Netherlands without special provisions.

Pieter Holsteyn the Younger (1614-1673), pupil of his father Pieter Holsteyn the Elder, practiced his art in his native Haarlem as well as in Zwolle, Enkhuizen, Münster and Amsterdam. He became especially known for his engraved portraits and his watercolour paintings of birds and flowers. He created this drawing for a so-called “Tulip-Book.” These albums were made, on the one hand, at the request of wealthy garden owners, simply to document their treasures. Others were used by commercial growers as catalogues for the bulbs they sold.

Provenance:

By repute this drawing originates from the Krelage Collection. The Krelage nursery was founded in Haarlem in 1811 by E.H. Krelage (1786–1855) and gained national and international renown for its flower bulbs, lilies, and dahlias. The nursery won more than 800 medals at world exhibitions and horticultural shows and supplied royal courts across Europe. Among the many new hybrids they cultivated, the famous Darwin tulips stand out. The Krelage Collection was established in the mid-19th century by nurseryman Jacob Heinrich Krelage (1824–1901) and was later continued by his son, Dr. Ernst Heinrich Krelage (1869–1956).

Price: Euro 9.750,- (incl. frame)