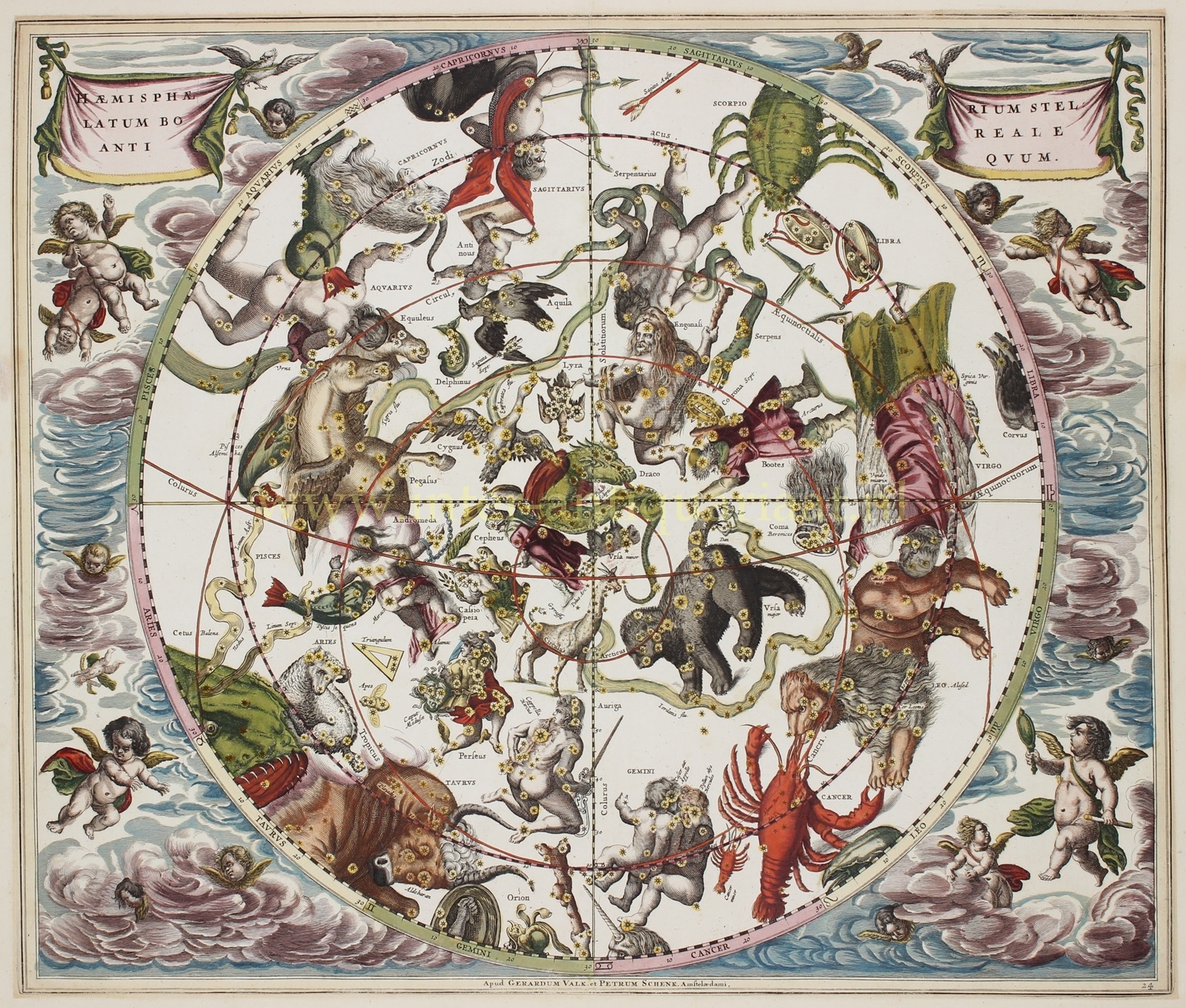

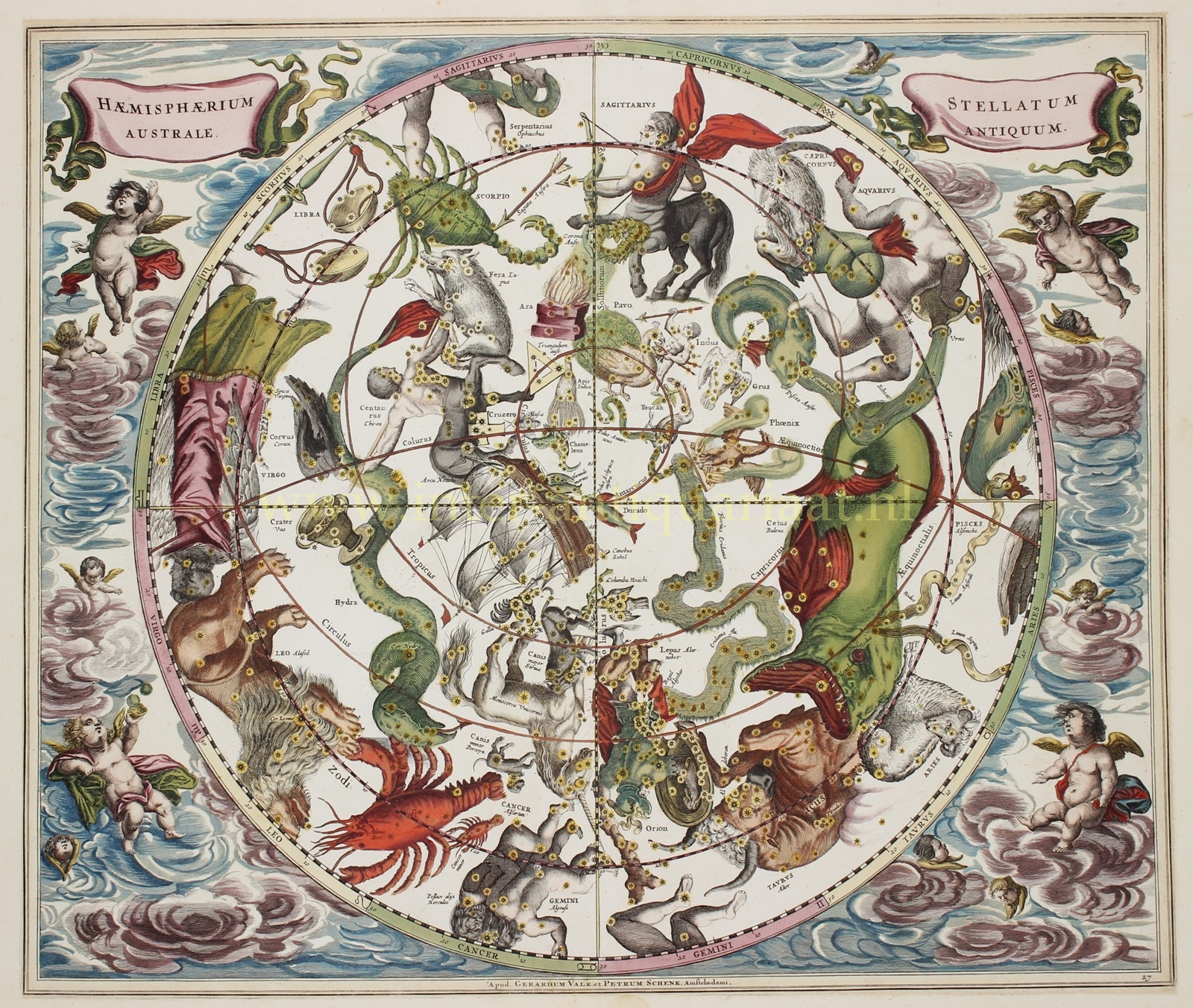

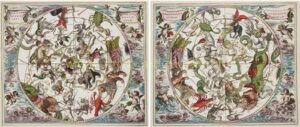

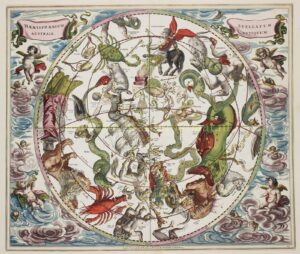

“Haemisphaerium Stellatum Boreale Antiquum” [starry northern hemisphere of antiquity] and “Haemisphaerium Stellatum Australe Antiquum” [starry northern hemisphere of antiquity], copper engravings made by Andreas Cellarius as part of his Atlas Coelestis seu Harmonia Macrocosmica [Celestial Atlas or The Harmony of the Universe], published by Gerard Valck and Pieter Schenk in 1708. With beautiful original hand colouring. Size (each): 43,5 x 50,5 cm.

Little is known about the creator of the most beautiful celestial atlas ever published. The only thing we know for certain is that Andreas Cellarius came from the Palatinate region in Germany and that when his celestial atlas with twenty-nine charts was published, he was the headmaster of the Latin school in Hoorn in Holland, earning a salary of 200 guilders per year. Beyond this, his life remains a mystery, although there are indications that he may have previously created an atlas of Poland.

The Atlas Coelestis contains charts of the so-called Ptolemaic universe, the Copernican system, and Tycho Brahe’s compromise between the two systems.

In “Hemisphaerium Stellatum Boreale Antiquum“, Cellarius depicts the constellations as they appeared in the northern hemisphere sky during antiquty, visible up to a latitude of 30° south. The Arctic Circle, the Tropic of Cancer, the equator, and the ecliptic are also drawn. In addition to the Ptolemaic constellations, their corresponding mythological figures are illustrated, such as Antinous, Perseus, Engonasi (Hercules), Boötes, the rivers Tigris, Euphrates, and Jordan, as well as more familiar constellations like Pegasus, Andromeda, Cassiopeia, Ursa Major, Cancer, Gemini, Sagittarius, and Aries.

In “Hemisphaerium Stellatum Austale Antiquum“, we see the constellations as they appeared in the southern hemisphere sky during, visible up to a latitude of 30° north, including the Monoceros, Orion, Scorpius, and Hydra. The Antarctic Circle, the Tropic of Capricorn, the equator, and several ecliptics are also drawn.

Cellarius himself was not an astronomer, and his work has more decorative than practical astronomical significance. The atlas lacks a system that would allow an astronomer with a telescope to locate a star. Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens was dissatisfied with Cellarius’ work. The moon of Saturn he had discovered, Titan, was omitted, and some engravings contain spelling errors and perspective distortions.

The beautiful engravings were sold separately and often bound by collectors into a single volume with the atlas pages of Joan Blaeu. In this form, but also as separate celestial atlases, they found their way around the world. Thus, the Cellarius atlas can be found in the libraries of the Vatican and the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul.

The engravings remind us of the existence of countless now-forgotten constellations. In later descriptions, these were omitted, merged, or given different names. Cellarius and his publisher Johannes Janssonius were working on a second volume of the celestial atlas, but due to Janssonius’ death in 1664, it was never completed. The first (and thus only) volume was reissued by Pieter Schenk and Gerard Valck in 1708. Schenk and Valk left the maps unchanged, except for adding their names at the bottom.

Cellarius’ charts are the most sought after of celestial charts, blending the striking imagery of the golden age of Dutch cartography with contemporary scientific knowledge. If fact, they represent the high point of not just Dutch celestial maps, but all artistic renditions of the celestial skies.

Price: Euro 7.950,- (voor both northern and southern hemisphere together, incl. 2 frames)