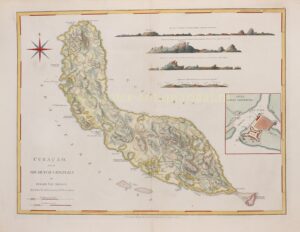

Curaçao – Robert Sayer, 1775

€3.450

CURAÇAO, DUTCH WEST INDIA COMPANY BASE FOR TRADE AND PRIVATEERING

“Curaçao, from the originals of Gerard van Keulen“. Copper engraving made by Thomas Jefferys published by Robert Sayer in London in 1775 as part of “The West India Atlas”. With original hand colouring. Size: 47 x 61 cm.

Map of Curaçao, with an inset of a map of Fort Amsterdam located on the Sint Anna Bay on the right. At the top right we see a number of coastal profiles, three of Curaçao seen from different directions and one of the uninhabited Klein Curaçao. At the bottom left there is a scale in Sea Leagues (1609 m) and Dutch miles (7157 m). Many bays around the island are noted on the map, a number are marked “for Barks” or “for Boats and small Craft”. An anchor has been drawn in various places along the south and west coast. Also indicated are the plantations, salt pans, water sources and vegetation.

The trade in textile, consumer goods, building materials and the like, which was always in need in Venezuela but also elsewhere in the Caribbean and which were exchanged for agricultural products, formed the basis of the Curaçao economy throughout the 18th century. The harbour quays became important meeting places for traders and seafarers from all places and regions. Not only the loading and unloading of ships provided employment. There were shipyards along the banks of Sint Anna Bay where ships were built, repaired or given new equipment. Deliveries of ship’s supplies and fresh water provided income for others. Furthermore, financial transactions took place and insurance policies could be taken out. In short: trade and shipping and related activities formed the basis of the Curaçao economy. These activities are concentrated in a small area on either side of the Sint Anna Bay, where the walled city of Willemstad arose. At the entrance to the harbour was Fort Amsterdam, for which the foundations had been laid shortly after the arrival of the Dutch West India Company (WIC) in 1643. The governor lived inside the fort, as well as the administrative offices of the WIC. It also housed most of the garrison, which in the 18th century usually numbered little more than 100 soldiers. Within the city walls of the district to the east of Sint Anna Bay, population increased sharply in the course of the 18th century. At the end of that century, nearly 5,000 people lived in less than 300 houses.

Thomas Jefferys was one of the most important English publishers of maps in the 18th century. He made maps of the entire world, but his best work is of North America and the West Indies. Starting his career in the map trade in the early 1730s, he worked as an engraver for several London publishers and eventually started his own shop. In 1746 he was appointed geographer to the Prince of Wales and became geographer to the King in 1760. This gave him access to the manuscripts and cartographic information in the possession of the English navy. In the early 1760s he embarked on an ambitious project to produce maps on the basis of new research of a range of English counties, but ran out of money and went bankrupt in 1766. He then collaborated with the London publisher Robert Sayer, who produced much of Jefferys’ maps that were reissued until after his death in 1771.

Jefferys made this map after a map by Gerard van Keulen, who had made his “Nieuwe Afteekening van het Eyland Curacao” in 1728.

Price: Euro 3.450,-