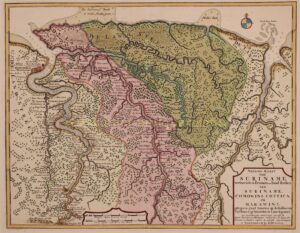

“Nieuwe Kaart van SURINAME vertonende de stromen en land-streken van SURINAME, COMOWINI, COTTICA en MARAWINI gelegen in Zuid America op de kusten van Caribana 6 gr. Benoorden de Linie Enquinocqt.” [New Map of Suriname showing the rivers and territories of Suirname, Comowini, Cottica, and Marawini located in South America on the coasts of Caribana 6 degrees North of the Equator.] Copper engraving made by Joachim Ottens, published in Amsterdam ca. 1715. With original hand colouring. Size: approx. 40 x 50 cm.

There was a time when adventurous, fearless, profit-seeking Europeans sailed into the open world, planted their flags on foreign shores, and then considered that land their own. The local population usually didn’t benefit much from this. Moreover, large numbers of slaves were often brought in from elsewhere to work under inhumane conditions on plantations. It’s difficult to imagine today that it happened like this, but Suriname is a striking example.

The area we call Suriname, or rather the northern coast of the South American continent, was first sighted by Europeans in 1499. They were initially not very impressed and disregarded the area. That changed when fantastic stories began circulating about El Dorado, the land where gold was supposedly abundant. Inspired by this, many Europeans in the 16th century ventured again to try their luck in what was then called Guyana. Portuguese and Spanish initially had the upper hand, but later, English, French, and Dutch also headed in that direction. They made contact with the local population, established a few settlements, and engaged in some trade. Most of the conflict occurred with the Spaniards and Portuguese, who, according to the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494, still considered the region as ‘theirs’ and didn’t tolerate intruders.

However, the English succeeded in colonizing Suriname in the mid-17th century. With the establishment of sugar plantations, they had gained experience elsewhere in the Caribbean: they put slaves to work, and in a short time, a part of the land was drained and a large number of plantations were founded. The Dutch also had great interest in this area. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665-1667), a fleet sailed from Zeeland to South America with the aim of conquering Suriname, which relatively easily succeeded in 1667. In July of that year, the Treaty of Breda was signed, formalizing this situation. The years thereafter show a rather chaotic and volatile picture of the colony’s administration by the Dutch. A new phase began in 1683 when the Society of Suriname was established, representing three parties simultaneously: the Dutch West India Company, the city of Amsterdam, and the Van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck family. The charter of this society regulated the powers of the colonists, which included a considerable degree of autonomy not comparable to other colonized areas in the East Indies (present-day Indonesia) and North America (the region around New Amsterdam). Attempts by the Society of Suriname to attract other settlers to establish themselves in Suriname met with limited success, and it was not always just the Dutch. Huguenots and Germans also settled in Suriname, as did a relatively large number of Jews. Because of this, the European community in Suriname showed little cohesion. At the end of the 18th century, there were about 3,300 Europeans living there, compared to tens of thousands of slaves who were working on the plantations under shameful and poor conditions. It wasn’t until July 1, 1863, that slavery was abolished. The Netherlands was one of the last countries in Europe to do so.

The map names a large number of plantations along the Suriname, Commewijne, Cottica, and Marowijne rivers. Remarkable is the “Ioods Dorp en Sinagoge” (Jewish Village and Synagogue) on the Suriname River, surrounded by a large number of plantations with Jewish owners (as indicated by Spanish-Portuguese names like Abram de Pina, Barug de Costa, Serfatyn, etc.). Also interesting is the mention of the people at Moroux Creek: “this people is very barbaric and vengeful.”

The map was made by Joachim Ottens (1663 – 1719), who learned engraving at the publishing house of Frederick de Wit and started his own business in 1711. His sons Renier and Josua Ottens took over from their father and became known for the production of extensive multi-volume atlases on demand, fortification- and pocket atlases.

Price: Euro 1.450,-